13 May Spinoza and Anders in Tuscany

For the second time, I had the pleasure of attending the summer academy of the School of Philosophy to take part. The trip took us to the vicinity of Florence where, under the expert guidance of the philosophers Bernd Waß and Heinz Palasser, we were able to enjoy a week of intellectual world experience and pure joie de vivre. In dreamlike surroundings, we devoted ourselves to Baruch de Spinoza, one of the founders of modern religious criticism, and Günther Anders, whose criticism of technology has lost none of its topicality in the context of our time.

REVIEW OF THE 10TH SUMMER ACADEMY OF THE SCHOOL OF PHILOSOHPHY – TUSCANY, ITALY, 2024

LIFE AND WORK OF BARUCH DE SPINOZA AND GÜNTHER ANDERS

Would it not be appropriate to the grandeur of creation to arrive at a life that follows the truth of what is real, not the interpretation of those who pose as authorities and who pretend to have seen through what is inscrutable?

And would it not therefore be epochal to finally overcome the dark night of ignorance, to be citizens of this world, not strangers who have to ask others for directions if they do not want to miss their goal? Inspired by this idea of self-determination, Spinoza seeks to uncover the background conditions that are needed to make it fruitful for a humanity that, like a marionette, hangs for the longest time on the string of the all-powerful. And so, in metaphysics and epistemology, he provides us with the philosophical foundation of freedom: a transparent God who cannot refrain from doing anything he does, a transparent creation based on this, in which things are done correctly, namely in accordance with natural law, and a cognizing spirit in which the world is reflected a priori – independently of the distorted images of perception. However, as beings destined by God to live, we are not only spiritual but also physical beings who, embedded in the totality of nature, find themselves confronted with an external world that threatens to destroy them. Affected by this, we become entangled in a web of affects, or rather passions, woven by the power to exist, this powerful striving to maintain our own existence for an indefinite period of time. Like the prisoners in Plato’s cave, we take the false for the true and the bad for the good, we are not masters of ourselves but driven, unable to find peace. A tragic fate, one might think, although not without a way out, because what remains for us to escape the interplay of insatiable desires, foolish pleasures and destructive grief and to free ourselves from the bondage of more than just the emotions is the path of reason. To make use of it, to allow ourselves to be guided by it, that is to turn from the ignorant into the wise, into a person who possesses nothing less than true knowledge. Such a man, who is able to see himself, the outer world and God, sub specie aeternitatis, is free in every respect and satisfied to the highest degree, and only he leads a life that can be called a successful, i.e. a blissful one.

And we, who have studied and labored over this epochal philosophical legacy of modern times? If there was still something to do, if we wanted to reduce Spinoza’s ethics to a single – Enlightenment – imperative, if we wanted to summarize our quintessence in a final sentence, we could, without having to fear the censure of this great philosopher, have the Roman poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus appear and shout at the top of his voice: Sapere aude! Dare to be wise!

But all wisdom – if we are ultimately able to attain wisdom at all nothing will help us. We must perish – humanity as a whole and therefore also every single one. At least if we believe Günther Stern’s findings.

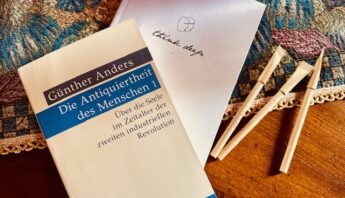

Günther Stern, once married to Hanna Arendt, whose pen name was Günther Anders and under which he published exclusively, draws a gloomy picture of the state of the soul in the age of the second industrial revolution in his main work “The Antiquity of Man”. His radical critique of technology and progress stems from an existentialist anthropology, a psychology of man as a being in relation to products manufactured by machines, an economic ontology and an epistemology of the mind: while the world is fixed in everything, man is only fixed in not being fixed in anything. On the one hand, this is the foundation of his freedom and his ability to understand himself as an individual, but on the other hand it is also the reason for his radical alienation, his anthropologically ineluctable not-fitting-into-this-world. Since man does not fit into this world, he must create a world for himself. But because he is not fixed, it is also not the world that he creates for himself, and so he must constantly create something new without ever reaching his goal. Nonetheless, he is bound to the world, and this binding is reflected in his hunger – his hunger for the world. His sheer neediness drives him on, and in order to satisfy it, he must possess the world. A diabolical cycle that has already progressed to the end times, i.e. the third and final industrial revolution:

Machines produce machines that produce machines; until a final machine produces something that is not a machine but a product: bread or grenades. Products are consumed in the hunger for the world, which triggers the manufacturing process of the machines anew, ad infinitum. In this way, the machines themselves become subjects

and the imperative of the products they produce is: consume me! Now the hellfire of demand is being stoked in the laboratories of the advertising industry and man is being turned into a consumer, a mere employee who consumes day and night and who ultimately destroys himself in the process. Anders’ main theses are based on this finding: That we are not up to the perfection of our products; that we produce more than we can imagine and take responsibility for; and that we believe we are allowed, no should, no must, do what we can. The fact that this is indeed the case is shown firstly by the Promethean shame and the dehumanization that goes hand in hand with it. Man is ashamed of having become, instead of being made, a begotten instead of a legitimate product, a human being instead of a precisely functioning, rebuildable, reproducible device on a par with other devices. And so it strives to eradicate its natural shortcomings, to overcome itself, to reify itself, to desert into the camp of devices. Secondly, the dictate of the mass production and reproduction of commodities and the concomitant utilization of everything and everyone – once is not once, is the first axiom of economic ontology: the unique is not; the singular belongs to non-being; only in the plural, only as a series is being. Being, however, is being a raw material, and what has had its day as a raw material – people as well as radium-contaminated nuclear waste – becomes dead weight, a liquidation slag in the merciless production process of commodities. And finally, thirdly, it is shown by the fact that in a highly complex world with a high degree of division of labour, what is technologically possible is always realized. The individual specialist worker has long since lost sight of the whole and regards his tiny contribution – excluded from the possibility of a conscience – as (morally) clean. The production and use of the atomic bomb is the only thing standing in the way of the apocalypse, to which we are blind because the capacity of our minds is limited: the large number of people involved and the complexity of the production process prevent any prevention.

In the face of this devastating drama, you want to flee, to take a vacation from morality with Günther Anders, to escape to an island of the blessed, to leave the misery behind. Only understandable. But his critique of technology is not an ethics of technology, but an anthropology of doom, and not the smallest piece of land will remain. Not least for this reason, the great humanist Anders, who always had people in mind in his philosophizing, writes that he hopes he is wrong in all his theories.

LITERATURE:

– De Spinoza, Baruch: Ethik in geometrischer Ordnung dargestellt, Meiner, Hamburg, 2010.

– Waß, Bernd: Intelligibilität und Freiheit, Über die Ethik des Baruch de Spinoza, Tredition, Ahrensburg, 2023.

– Anders, Günther: Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen, Über die Seele im Zeitalter der zweiten industriellen Revolution, C.H. Beck, Munich, 2024.